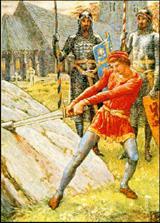

Explorations in Arthurian Legends

A Literature Review

Part 6: Sir Thomas Malory

|

|

One author who definitely echoed the signs of his times in his Arthurian writings was Sir Thomas Malory. Arthur looks a bit like Henry V, who was king at the time Malory was writing; and Arthur's route through France echoes Henry's moves toward Agincourt.The action, of course, takes place against the backdrop of King Arthur's Court, which Malory places at Winchester. The ideas of chivalry and courtly love are in full flower here, as they were in other stories in England in the 15th century. Did he intend his tales to be one cycle, echoing the styles of Robert de Boron and the Vulgate authors, or did he write tales one at a time and then decide later on that an effort at unification was necessary? No one knows for sure. Another raging debate among scholars is which Thomas Malory wrote the works? Four men of that name are possible suspects; the one from Warwickshire (despite his prison convictions) is believed to be the author. Whoever he was and whatever his intentions, "Malory" left us with a large body of work, which, taken together, comprise quite possibly one of the finest works ever written in the English language. |

Malory was writing in the right place at the right time. The printing press was just making its way to England, and a man named William Caxton was looking for books to print.

|

As with the Vulgate Cycle, Arthur is the supreme leader, reigning over all. Having kept this device, Malory is free to make Lancelot the central character. We first meet him in the Tale of King Arthur and the Emperor Lucius, in which he makes his name as a hero of the Roman Wars and cements his reputation as first knight of the Round Table by many chivalrous deeds thereafter. Lancelot gets his own tale, The Tale of Sir Launcelot du Lake, a three-sectioned work in which we recount the French Lancelot, meet his nephew Lionel, and see the great knight perform all sorts of chivalric adventures. |

|

With Malory's treatment of Lancelot comes a departure from the spiritual passion seen in the Vulgate Cycle: Malory emphasizes Lancelot's relative success, not his ultimate failure.

|

|

Malory treats Tristram and Iseult not as a tragedy but as an illustration of the greatness of the ideal of courtly life and love. Tristram is one of the four best knights of the world, and he loves Iseult as amatter of course, not as a matter of the passionate heart. Mark is, of course, a figure in the tale; but the ending is a glimpse of the lovers at Joyous Gard, Lancelot's stronghold. Their tragic end is remarked on only at the end of Lancelot and Guinevere. It is Mark who gets the rough treatment: Malory makes him out to be so much of an unsympathetic character that the conduct of his wife toward her lover can almost be justified. |

|

In the last tale, it is a chance slithering of a serpent that undoes the moment: Arthur and Mordred, meeting to discuss a truce, give orders that the drawing of any blade means war; one of the knights in attendance at the truce conference sees an adder and draws his sword to kill it, lest it kill him; both sides see the glint of steel and assume the worst. Malory goes out of his way not to say what happened to Arthur in the end. He says Mordred died on the field of battle, and he says Arthur was mortally wounded and taken away. Yet Bedivere later meets a gravedigger and assumes that the grave is being dug for Arthur. Is he dead, or is he coming back? You decide. |

|

In Malory, then, we see the tragedy exposed to the raw. Yes, the knights seek the Holy Grail. Yes, the main characters are fallible. Yes, they do horrible things. But the overall theme is chivalry and tragedy, not sin and repentance.

Malory used all the popular sources in writing his tales. Here is a breakdown:

Malory is a giant in the field. He is the basis

for a great many modern authors, as Geoffrey of Monmouth for a great

many authors in centuries past. Taking a cue from Malory a few

hundred years later was none other than Alfred,

Lord Tennyson.

|

The Politics of Violence in Malory The Changing Role of Women in Arthurian Literature |

Back to

Explorations in Arthurian History and Legends

Main

Page

Other